Is Jess Phillips a Pakistani Rape Gang Facilitator?

When Fourteen Years of Knowledge Meets Misconduct in Public Office

Jess Phillips has introduced a word back into the public conversation. Facilitators.

She uses it to describe the people who knew children were being raped, knew the abuse was organised, knew it was happening in plain sight, and did nothing. Those who turned a blind eye. Officials who protected institutions. Authorities who ensured nothing happened.

The distinction matters. A collaborator actively cooperates with wrongdoers. A facilitator makes wrongdoing easier through inaction, obstruction, or institutional protection. Collaboration requires participation. Facilitation requires only knowledge and the authority to act.

Both carry moral weight. Both enable harm. But facilitation often hides behind process, procedure, and the protection of institutional reputation. It is the more insidious crime because it wears the mask of respectability.

She says these people must be “held to account”. The question is whether that word now applies closer to home.

What Phillips now openly admits

On 2 September, in the House of Commons, Jess Phillips, the Minister responsible for safeguarding women and girls, made a series of admissions that are as shocking as they are damning.

She confirmed she has met survivors who alleged that police officers were not just complicit in the rape gang scandal but were perpetrators of rape themselves. She admitted she personally witnessed cover-up behaviour in grooming gang cases. And then she claimed Pakistanis had been the most fervent truth seekers in exposing the abuse, a statement that drew immediate backlash from survivors and campaigners.

Just weeks earlier, on 2 June, Phillips told Parliament she had been “waiting 14 years for anyone to do anything.“ Fourteen years. Her own words. Fourteen years of knowing. Fourteen years of silence.

In her latest Sky News interview, conducted by the notably sympathetic Beth Rigby, Phillips concedes several facts that are no longer contested.

- That grooming crimes were widely known.

- That children were advertised by word of mouth. That men gathered openly in cafés and taxi firms.

- That institutions knew and failed to act.

- That facilitators existed, including politicians and police.

Rigby supplies the framing. Phillips accepts it.

Her parliamentary testimony goes further still. “I have seen this with my own eyes… People have said, ‘Oh, it might cause trouble.’ I have definitely seen this, and it should never have been allowed to happen.”

Across Parliament and broadcast media, the pattern is consistent. These are not accusations made by campaigners. They are her own words, given under parliamentary privilege. Knowledge is no longer disputed. Neither is the awareness that exposure “might cause trouble”.

The fourteen-year problem

Phillips has previously been forced to admit she knew about organised child sexual exploitation for fourteen years. Fourteen years. That matters, because once knowledge is established, the issue is no longer awareness or outrage. It is duty.

During those years, survivors in Oldham called for a public inquiry. Those calls were blocked. Accountability was delayed. Institutions were protected.

Later, when pressure grew for a national inquiry, the same pattern followed: resistance, dilution, containment.

This was not passive history. It was active decision-making.

Your support doesn’t just fund writing. It keeps this work free for all, and ensures that truths the powerful want erased are dragged into the open.

The inquiry defence and why it fails

When challenged, Phillips reaches for a familiar line. “The law is not retrospective.” It sounds authoritative. It is also misleading.

No new law is required to prosecute public officials who knowingly failed children. Because Misconduct in Public Office already exists.

“Yes… legally“

Pressed on whether those partly responsible could be brought to account properly, Phillips replies: “Yes yes yes… legally I know it…“

But legally is never defined. She names no offence, sets out no prosecutorial pathway, references no existing power. The CPS is not mentioned. Police referral is not mentioned. Misconduct investigations are not mentioned.

Instead, the answer dissolves into process: chairs, consultations, drafts, scope. Accountability becomes procedural. Justice is deferred.

The law they refuse to talk about

Misconduct in Public Office is a long-established common-law offence. It applies where a public officer knows of serious wrongdoing, holds authority or responsibility, wilfully neglects their duty or wilfully misconducts themselves, abuses the public’s trust, and acts without reasonable excuse.

The maximum sentence is life imprisonment. This offence existed throughout the grooming gang years. It is not retrospective. It does not require new legislation. It does not care about political embarrassment. It cares about duty and neglect.

Where facilitation actually begins

Facilitation does not require participation in abuse. It requires knowing inaction or obstruction. The issue raised here is not personal culpability for abuse, but the knowing failure to act once aware.

If a public official knows children are being raped, knows institutions are failing, and then uses their authority to block, delay, or dilute accountability, that is not a policy disagreement. That is wilful neglect of duty.

This is not a question of political disagreement, but of criminal thresholds. That is precisely what Misconduct in Public Office was designed to address.

Oldham was not an abstraction

Opposition to a public inquiry in Oldham did not occur in a vacuum. It occurred in the context of established evidence, survivor testimony, police and council failures, and national awareness. Blocking scrutiny once knowledge exists is not neutral. It is containment. Jess Phillips can try as much as she want to, she cannot re write this.

The national inquiry sleight of hand

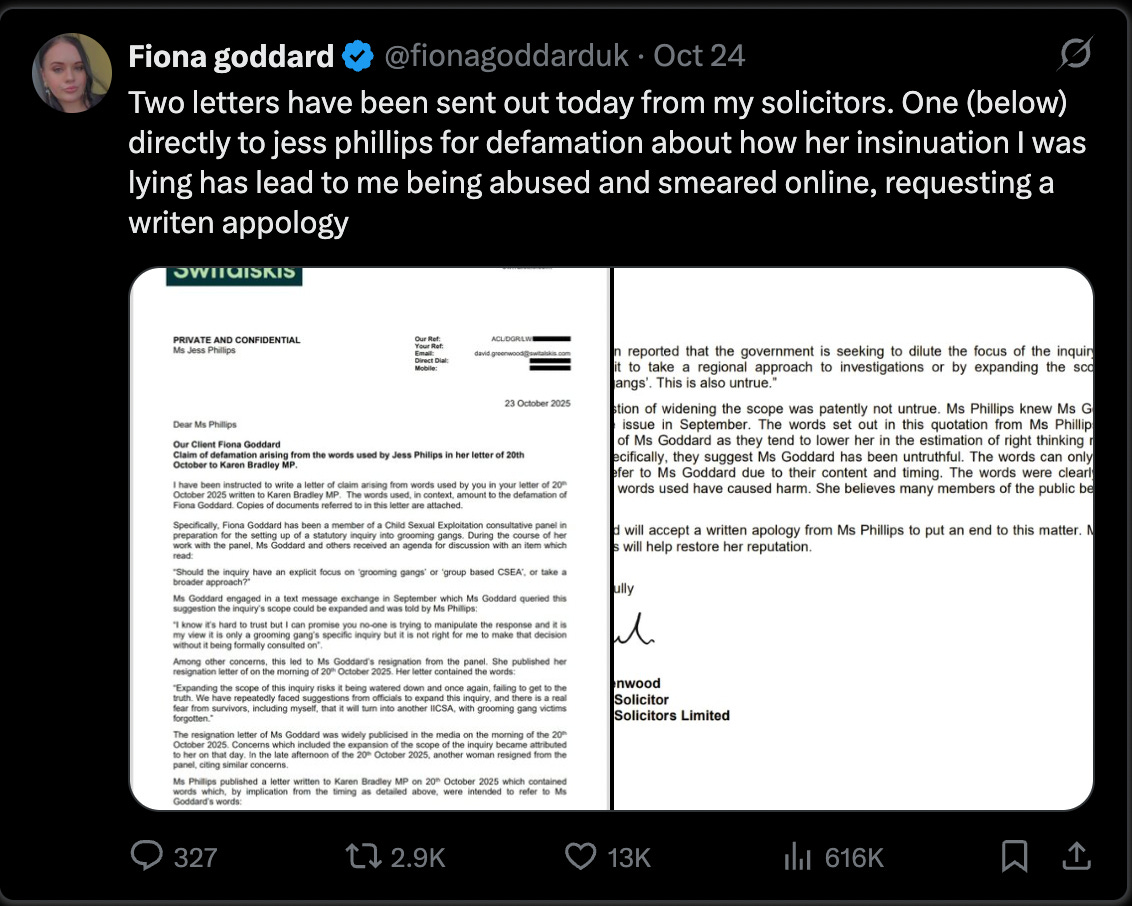

Phillips claims survivors were involved in drafting the inquiry’s terms of reference. They were not.

What followed instead was more serious. Five survivors resigned from the government’s own survivors panel in protest at how the inquiry was being handled and publicly called for Phillips’ removal from post. Their resignations were not symbolic. They were explicit statements that the process had lost credibility and that survivors were being used, not listened to.

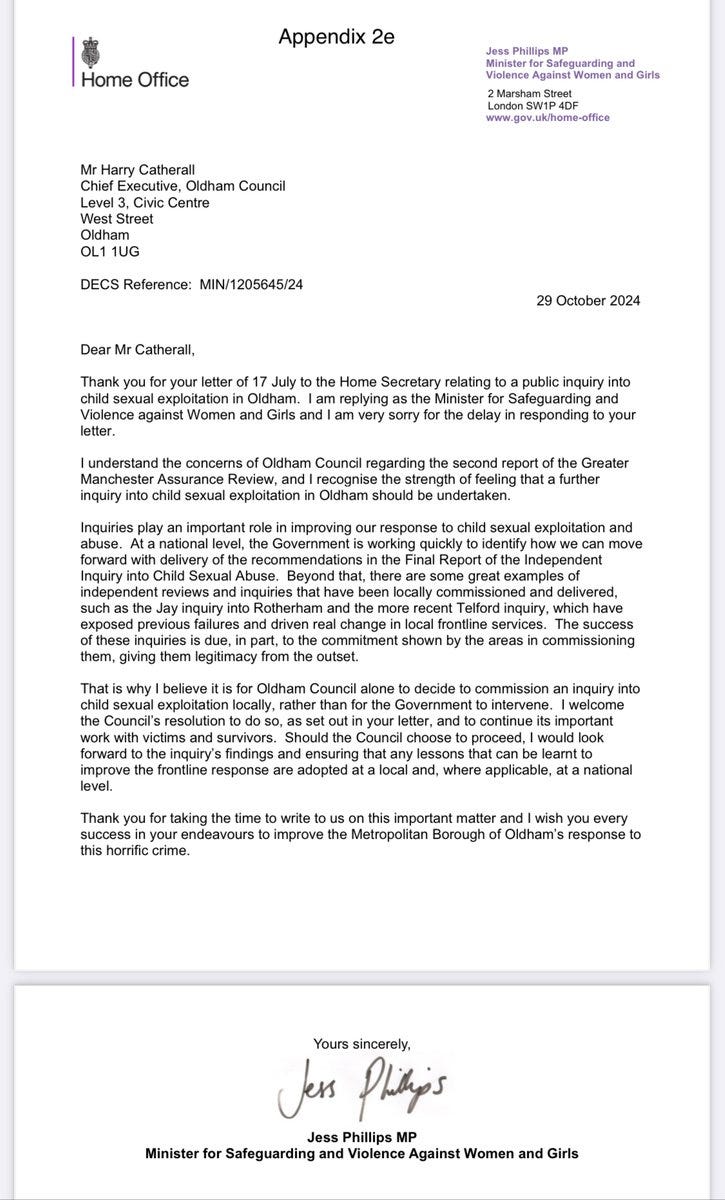

One survivor, Fiona Goddard, went further, threatening legal action after Phillips publicly accused her, a survivor of organised sexual abuse, of lying. The evidence that followed did not support Phillips’ claim. It showed that the survivor’s account was accurate, and that it was Phillips’ statement that was false.

This matters, because Phillips’ repeated assertion of survivor involvement rests entirely on claim, not fact. The government’s survivors panel was not consulted on the draft terms of reference, was not involved in appointing the chair, and was not given meaningful influence over scope.

Yet survivors were repeatedly invoked to legitimise the process. This is not consultation. It is procedural laundering.

And when survivors objected, publicly, collectively, and at personal cost, they were dismissed, accused, or ignored. That is not a misunderstanding. It is a pattern.

“Holding people to account“ without consequences

Phillips repeatedly says the inquiry will “hold people to account”. But listen carefully to what that actually means: exposure without prosecutions, findings without criminal referrals, conclusions without retrospective accountability, recommendations without consequences beyond reputational damage.

Exposure without justice is not accountability. It is closure for institutions, not survivors.

The far-right manoeuvre

When scrutiny turns uncomfortable, another actor enters the frame. The far right.

Phillips introduces it in two distinct ways. First, criticism of her handling of grooming gangs is subtly reframed as existing in a hostile political environment: cynicism, pile-ons, bad-faith actors exploiting the issue.

But the more serious move comes when the discussion turns to the police. Phillips acknowledges that victims told her police were not only covering up abuse, but in some cases were believed to be complicit. She then immediately adds that some victims believed their information had been passed on to far-right campaigners.

This matters. Allegations of police misconduct are no longer treated as matters for investigation. They become beliefs, circulating in a politically toxic space. Scrutiny becomes risk, not responsibility.

And then the manoeuvre becomes obscene. Because the far right were not the men gang-raping these girls, advertising children by word of mouth, gathering openly in cafés and taxi firms, or embedding themselves in councils, police forces, and safeguarding institutions.

Yet at the moment accountability is raised, the far right are invoked anyway, not as perpetrators, but as a rhetorical shield. This is not analysis. It is deflection.

The unavoidable question

Put the record together: Phillips has acknowledged the knowledge, admitted facilitators existed, conceded institutional failure, blocked or diluted inquiries, excluded survivors while invoking them, and ignored existing criminal law.

At that point, the question is no longer rhetorical. If a public official knows children are being raped, knows institutions are failing, blocks inquiries that could trigger prosecutions, misrepresents survivor involvement, and ensures consequences never materialise, what is that if not facilitation?

The sentence they hope you never read

The law does not need to be retrospective. Misconduct in Public Office has always been sufficient to prosecute politicians, police officers, and officials who knowingly allowed children to be raped. The maximum penalty is life imprisonment.

That fact, and the silence around it, explains everything.

A final clarification

This article does not declare Jess Phillips guilty of a crime. That is for investigators and courts. What it does is something far more dangerous to power. It takes her words seriously. It applies the law she avoids. And it notices when obvious questions go unasked.

Is Jess Phillips a facilitator?

If the question makes people uncomfortable, it is because the law has finally been allowed into the room.

But perhaps the question is too narrow. If a public official with direct ministerial responsibility for safeguarding girls knows children are being raped for fourteen years, actively obstructs accountability, misrepresents survivor involvement, and uses their authority to ensure consequences never materialise - at what point does knowing obstruction become active cooperation?

At what point does facilitation become collaboration?

Perhaps some politicians and public officials should be tried not merely as facilitators, but as collaborators? The distinction matters less than the duty. And the duty, for fourteen years, was abandoned.

I am Raja Miah. For seven years, I led a small team that exposed how politicians protected the rape gangs. Prior to this, I spent over a decade of my life trying desperately to safeguard communities from violent extremists.

I am not a commentator. I am more than just a campaigner. I cannot do this without you. I need you to stand with me. We’re running out of time. Without the numbers, they will win. It’s as simple as that.

🔴 Subscribe to my newsletter – it’s free. Or support the work if you can afford to do so. Whatever you do, please subscribe;

Red Wall and the Rabble is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is the fight. This is the moment. There will not be another.

🔴 Prefer a one-off contribution?

👉 http://BuyMeACoffee.com/recusantnine

👉 http://paypal.me/RecusantNine

No corporate sponsors. No party machine. Just you and thousands of ordinary people who know what’s at stake. We’ve come this far. Help finish it.

- Raja Miah MBE